Beyond reciprocal altruism: Herbert Anderson on empathy, trust & stories that define us

In C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia; The Silver Chair, Prince Rilian confronts an uncertain future and the reality of an absent leader by uttering a few lines that express a core theme in the life of Herbert Anderson: “Let us descend into the city and take the adventure that is sent us.”

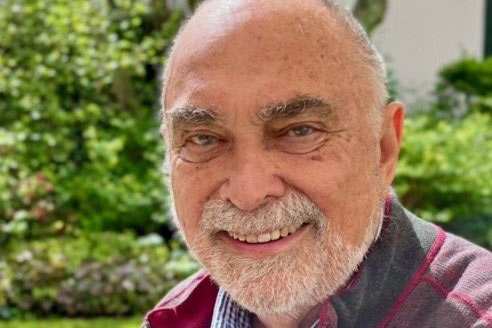

“Take the adventure that is sent you,” Anderson says again, “and then do with it what you can.” He knows well that the promise of adventure is two-sided. It’s perilous, to be sure; unpredictable. But taking on the adventures of your life creates the opportunity to define your convictions and then live by them. It will not be easy. But, as Anderson’s experience reveals, it is worth it. Anderson (1962, BD) will be awarded LSTC’s “Lifetime Service Award” Oct. 13 during LSTC’s Homecoming.

Anderson grew up in a parsonage in a small Swedish community in Minnesota. Because of his own life story, it was impossible not to ask the hard questions: Why are we here? What do we owe each other? How do we care for one another? And how do we invest ourselves in people and projects with a deep awareness that we are finite creatures? These questions led Anderson to develop his abilities to honor and empower the struggles and suffering that make us human, that build our character, and that link our stories with the Story of God.

In his ministry of teaching and writing, Anderson has not looked away from challenging topics such as grief, death and dying, and what he refers to as ‘maladies’ of the soul like loneliness, cynicism, and despair. Beginning with All Our Losses, All Our Griefs in 1983, his focus never wavered from the shared experience we find in grief. “Grief is ordinary and unavoidable,” Anderson says, “and grieving is necessary although it is not easy.” Indeed, the universal connections that we build through understanding each other’s losses can be bridges to the kind of radical, unadulterated empathy that just might have the power to break down artificial barriers of racism, sexism, and xenophobia when all other remedies have failed.

Empathy and radical hospitality are also constant themes in Anderson’s practical theological and academic work writ large. It has been his good fortune to teach and practice ministry in a variety of ecumenical contexts. Through it all, he has sought to embody the conviction that we do not have our life as a possession: it is all gift. The rhythm of the Christian life is receiving and expending, receiving and giving. It’s something beyond reciprocal altruism, and yet the knowledge that in healing the whole you heal yourself cannot be ignored.

For Anderson, with scores of professional publications to his name, several awards, and 60 years as an ordained minister, a life of service is not about giving yourself away. It’s about setting yourself to the side to make space for another person. “It’s a lifetime journey,” he says with characteristic humility. “There have been good days and bad days in setting myself aside.”

With so much practice at putting others first, Anderson is visibly uncomfortable talking about his own accolades. However, in discussing the LTSC Lifetime Service Award he says, “To be recognized by the Church that brought me up and the Tradition that formed me – that matters.” Invited to reflect on his life, Anderson is surprised by his willingness to take adventures that he couldn’t see the end of, in pastoral work and in teaching. He is reminded of a line from the poet W.H. Auden: “To choose what is difficult all one’s days, as if it were easy. That is faith.” Anderson pauses. “Now, I’ve chosen difficult things to do…but I haven’t always done them as if they were easy.” But if he had, he might be finished, and it’s to the benefit of all who have the privilege of knowing, working, and studying with Herbert Anderson that his work continues. And it does.

By Rhiannon Koehler, a writer, editor and content director in Chicago.