Heralding Utopias: Immanuel Karunakaran’s Art of Wound and Witness

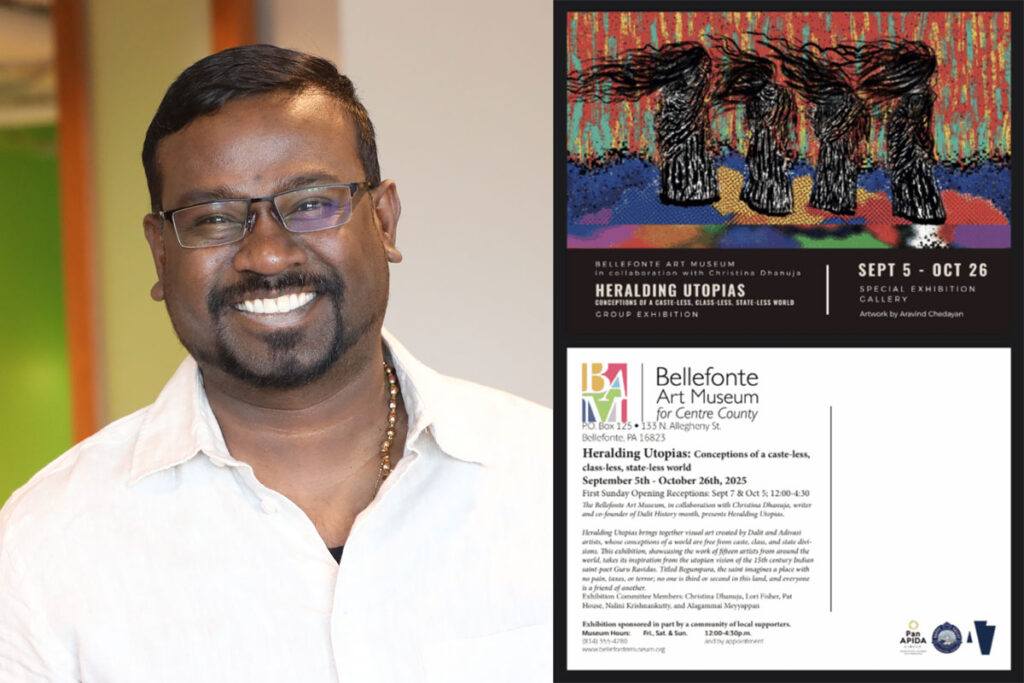

When LSTC PhD candidate and 2023 ThM graduate Immanuel Paul Vivekanandh Karunakaran steps into a gallery, he brings more than canvases. He brings testimony. This fall, his work will be featured in Heralding Utopias: Conceptions of a caste-less, class-less, state-less world at the Bellefonte Art Museum in Pennsylvania (Sept. 5–Oct. 26). The exhibition—organized in collaboration with writer and Dalit History Month co-founder Christina Dhanuja—invites viewers to imagine a social order beyond the hierarchies that harm and divide. Karunakaran’s answer is disarmingly direct: art that refuses to look away, and faith that refuses to give up.

A scholar in Ethics, Church, and Society, Karunakaran creates from the borderlands—where caste, race, migration, and memory converge. “My art is both wound and healing,” he says. “It holds pain open even as it gestures toward hope.” His pieces are not meant to soothe. They are meant to see—and to help us see—how bodies marked by caste and color endure, resist, and insist on life.

He found the exhibition through an ordinary scroll. “I first came across the Heralding Utopias exhibition through social media,” he says. “The theme immediately resonated with me because my work is deeply connected to ideas of both utopia and pragmatism. As a creator, I imagine a better world by exposing the realities of social death experienced by Dalit and Black bodies under oppressive systems. For me, the task is not just to dream of the future, but to challenge and question the present so that a different future can become possible.”

The work he’s sending to Pennsylvania is intimate and declarative all at once: three mixed-media portraits, each bearing the grain of lived experience. “All three works are portraits of people, because for me, bodies carry the deepest truths of survival, resistance, and imagination,” he explains. “I chose mixed media as my language of expression, since no single medium could hold the complexity of memory, migration, pain, and hope that shape my story.”

He names them like chapters. “Utopia Begins With Us is a declaration that justice and freedom are not abstract ideals waiting in the distance, but something we build with our own hands, in our own communities, starting now. Sankofa Unbound: Remembering to Rise draws on the wisdom of returning to the past to reclaim a future. It’s about carrying ancestral memory, refusing erasure, and insisting that remembering is itself a radical act of rising. Body Breaking Boundaries is the most intimate. It captures what it means to live in a body marked by caste and color in a society that draws lines meant to contain us. This body does not remain confined; it presses against walls, it spills over borders, it breaks through what was meant to silence it.”

He pauses, then tightens the point: “Together, these works are not only artistic expressions but also testimonies. They are born from the dissonance of being a Dalit in America—where oppression is layered, where belonging is fragile, and where resilience is constantly demanded. Yet within that struggle, there is beauty, resistance, and the insistence on life that refuses to be diminished.”

For Karunakaran, the show’s utopian frame is not ethereal. It’s contested ground. “As an artist, I cannot separate my work from the realities of Dalit life. Being Dalit myself, I know what it means to be bound by caste, class, and color,” he says. “Caste is no longer only an Indian phenomenon. It is one of the oldest systems of control, and though invisible to many, it remains embedded in the conscience of people everywhere. That is why imagining a caste-less, class-less, state-less world is not easy for us. Imagination itself is contested terrain. Reimagining is even harder.”

And yet, he insists, art lets him walk ahead of the present. “Art allows us to live in the future before it arrives. It becomes both resistance and healing. My work is political because it confronts systems that thrive on Dalit and Black social death. It is spiritual because it refuses to accept death as the final word. I work within what I call Dalit pessimism, which names the way caste, like white supremacy, structures life through erasure and denial. And still, I hold on to the paradox: in survival, we find resistance; in resistance, we glimpse hope.”

His Lutheran formation sharpens that paradox. “I am a Lutheran, shaped by a faith that has never been free of caste discrimination,” he says. “I have faced rejection, denial, and stigmatization within both the church and society because of my Dalit identity. That reality forces me to live in fugitivity, carrying the weight of being unwanted yet refusing to disappear. In that fugitive space, imagination becomes unstoppable. It does not wait for permission. It creates its own pathways of liberation, its own promises of revolution.” Then he reaches for a familiar cadence: “Dr. King’s words echo here: ‘I may not get there with you, but I have seen the promised land.’ My eyes, too, have seen glimpses of it. And through my art, I insist that we keep walking toward that vision, no matter how many walls try to contain us.”

His scholarship at LSTC—ethics braided with memory and responsibility—threads directly into the studio. “There is no one universal ethics,” he says. “That is what I am learning from Jesus of Nazareth, whose life itself disrupted the dominant moral frameworks of his time. My ethics is deeply grounded in Dalit and Black ethics, which continually challenge the dominant ethical discourse that has been shaped by privilege and power.” The line of formation runs through his family. “I grew up watching my mother, Rev. Unicy Karunakaran, endure the weight of patriarchy and caste discrimination in the church, and yet she carried herself with resilience and resistance. She taught me to see the Gospel through the eyes of those who suffer and to learn from the wisdom of mothers. My wife, Cynthiya, teaches me faith and endurance. My daughters teach me the core of love.” These are not acknowledgments tacked on at the end; they are the ground on which his canvases stand. “These are not just personal lessons; they are theological insights that shape how I write, how I teach, and how I create art.”

Living in the United States has clarified the intersections he names. “This society is built on race and racism, but in resisting racism, people often overlook or even reproduce caste hierarchies. Few recognize that Black bodies are positioned at the very bottom, effectively rendered outcastes. The intersections of caste and race are dangerous because they operate both visibly and invisibly. My art and theology together attempt to name these realities, to show how people are implicated, whether knowingly or unknowingly, and to invite new ways of imagining justice, love, and community.”

To be recognized publicly as a Dalit artist, he says, is itself an act of naming. “For me, being recognized as a Dalit artist is not just a label. It is a declaration of resistance,” he says. “Dalit does not only mean the broken, the oppressed, or those forced to the margins. The very reason these oppressions exist is because of our identity as those who are casteless, those who refuse to fit into the order of caste, and those who actively oppose it. Too often, people reduce the word Dalit to ‘lower caste,’ but that is a distortion. I am Avarna outside the varna system altogether. I am an outcaste.”

He does not flinch when he says what that declaration requires. “To claim Dalit identity is to reject caste in every form. It is to stand against its practices, its hierarchies, and its false promises of purity. For me, this recognition as a Dalit artist gives power, not shame. It strengthens my resolve to continue resisting and challenging caste through my art and theology. My creative work becomes both witness and tool, a way of breaking silence and carving out space for truth. Spiritually, this identity connects me to a long history of those who chose dignity over domination, and faith over fear. Personally, it reminds me that my art is not just self-expression—it is a continuation of a larger struggle for liberation. So yes, I am glad to be known in this world as a Dalit artist, because it tells the truth about where I come from, what I oppose, and what I hope for.”

Even the exhibition’s historical touchstone, the saint-poet Guru Ravidas, folds into his Christian imagination. “I did not grow up knowing much about Guru Ravidas, but his vision of Begumpura—a city without sorrow, caste, fear, or servitude—speaks directly to me,” he says. “It echoes the Christian promise of a new heaven and new earth, where the old order of suffering is no more.” The vision is not purely devotional. “For me, this vision is both spiritual and political. It insists that another world is possible, where dignity and freedom are the birthright of all. As a Dalit Christian, my art embodies the same hope: to resist despair, to reject caste and race as destiny, and to continue imagining the liberation Ravidas sang about.”

His leadership at LSTC—Graduate Student Association President, Antiracism Co-Chair, collaborator and curator—comes from the same creative core. “Leadership isn’t just about management or duty; it’s about imagination,” he says. “The same creative vision that influences my art also guides how I lead, collaborate, and challenge systems. I am both self-taught and self-formed. I don’t merely reproduce what has been passed down; I reimagine what could be. The artist in me is what makes me a leader, someone who sees beyond the immediate, unites people, and strives for justice through creativity and conviction.”

He is careful to honor the teachers and communities who midwifed that imagination. “During my early seminary formation, Dr. George Zachariah helped me delve deeply into my artistic expression. Later, at the master’s and PhD levels, Dr. Marvin Wickware guided me in bringing that creativity into academic discourse,” he says. “I appreciate the Council for World Mission for commissioning me as an artist, and I am thankful to my friends and co-artists Shawna Bowman, Sergio, and Catherine for their collaboration in curating the mural at McCormick Theological Seminary. I recognize my mentors at LSTC, especially Dr. Thomas, for providing me with the opportunity to exhibit my art for Black History Month. All of these people have shaped who I am today.”

What should visitors carry out of the Bellefonte galleries? He doesn’t aim for easy uplift. “The works I bring to this exhibition are not meant to soothe. They demonstrate how Dalits have learned to live with wounds unhealed, refusing to remain silent. What I want viewers to take away is not comfort, but confrontation: the chance to see, perhaps for the first time, the realities of caste and the lives of Dalit communities. My art is an intentional invitation to witness, to learn, and to be unsettled. If it leaves viewers with questions that trouble them and hope that stirs them, then it has done its work.”

Then, almost as a benediction for other artists, he adds a word of counsel that reads like a thesis for his own practice. “There is a saying that art is rarely recognized during an artist’s lifetime, and history often bears that out. But for Dalit artists, even after death, recognition is not guaranteed because our work is political, because it speaks truth to systems built on oppression,” he says. “That is why I would encourage artists to continue resisting through their work. Recognition may be delayed or may never come. Still, the act of creating itself is an act of defiance, an assertion of our humanity, and a witness to the liberation that is already emerging. In our art, we plant the seeds of justice, and one day, those seeds will bear fruit.”

At LSTC, we are grateful to witness those seeds rising in the work of Immanuel Karunakaran—canvases that carry wound and witness, and a vision resolute enough to keep walking toward a promised land, even now.