Rev. Dr. Brooke Petersen Heals Religious Trauma Through Ministry

By Adolfo Luna

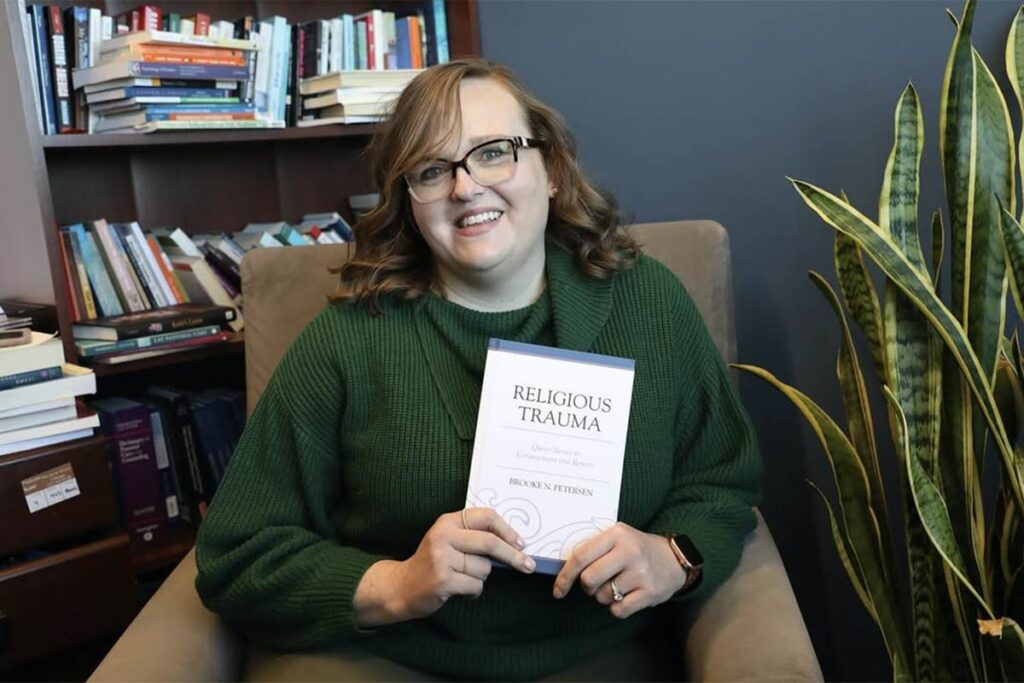

Rev. Dr. Brooke Petersen understands the profound mental health needs of today’s communities. Petersen, John H. Tietjen Chair of Pastoral Ministry, also believes that addressing mental health and trauma are part and parcel of the healing pastoral caregivers can offer. Through her dual expertise in pastoral care and clinical therapy, Petersen is preparing a new generation of church leaders at LSTC to meet contemporary challenges with courage and compassion.

“Moments of joy and deep suffering are intertwined in ministry,” Petersen reflects, recalling her early days as a parish pastor. These experiences sparked deeper questions, especially following the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s (ELCA) 2009 decision to ordain queer clergy. This milestone brought queer individuals into the church in greater numbers, including the trauma many had endured in previous faith settings. To better understand and address this lived experience of LGBTQIA+ individuals, Petersen focused the topic of her PhD research on religious trauma.

“The language of trauma fit the experiences that some queer people were bringing with them,” Petersen explains. Her work highlights how religious trauma manifests—feeling unsafe, a lack of focus, and disconnection—and how healing unfolds when inclusive spaces allow individuals to reclaim their narratives. Her book, Religious Trauma: Queer Stories in Estrangement and Return, examines these dynamics and offers practical insights for pastors and religious communities to help marginalized individuals find reconciliation and healing within faith communities.

“One needs to engage in explicit welcome – naming in a variety of ways that queer people are welcomed, beloved children of God,” Petersen says. This involves displaying visible symbols of welcome, participating in advocacy for marginalized groups, and repentance for the harms done by religion in the past. “We must help people reclaim their narratives and find love and connection where there was once rejection,” Petersen says.

At LSTC, Petersen integrates theological and clinical mental health principles. “Many people will turn to a pastor before seeking a therapist for their distress,” she notes. This underscores the importance of equipping clergy to recognize mental health challenges and to destigmatize seeking professional help. Petersen emphasizes that while pastors are not therapists, they play a critical role in bridging the gap. “We can offer the power of prayer, but also encourage clinical support as one of the tools God makes available to us,” she says.

As the director of candidacy at LSTC, Petersen also teaches students about the importance of self-reflection and personal wellness. She believes addressing one’s own mental health is not optional but central to effective ministry. “Mental health is not a side project; it is the project. You can’t model wellness for others if you haven’t done the work yourself,” she says.

Historically, pastoral care has focused on providing individual care, especially through stress or suffering. Petersen, however, sees opportunity in a broader approach; pastoral care that acknowledges collective struggles and societal injustices. Drawing on theologian Carroll Watkins Ali’s framework, she encourages students to consider the ways in which pastoral care can be nurturing, empowering, and liberating for individuals and congregations.

“For example, when students hear of policies that deny the existence of trans individuals, that is a call to respond,” she explains. For Petersen, pastoral care involves addressing systemic issues like racism, transphobia, and the rise of Christian nationalism because they cause suffering in communities and impact our collective wellbeing. “Our faith is not just an inside job—it’s an outside job. We must speak words of grace and truth in the public sphere,” she says.

Looking ahead, Petersen sees the integration of clinical pastoral care with traditional frameworks as a key trend within the field both inside and outside the ELCA. She also highlights the need for clergy to address the mental health crisis and resist forces that marginalize vulnerable communities.

“The needs of the world are immense,” Petersen concludes. “Whether the issue is about politics, climate change, or social issues, we can’t shy away from speaking truth to power. We must speak words of mercy and grace to remind the world of God’s love in the face of its deepest struggles.”

At LSTC, Petersen’s work is transforming pastoral care into a practice of liberation, healing, and hope, meeting the needs of a changing world with faith and resilience.